It's been nearly six months since right-wing politician, lawyer, and former media executive Jeanine Áñez declared herself the interim president of Bolivia following the coup that ousted sitting president and head of the Movement for Socialism (MAS) party, Evo Morales. Yet, in spite of significant time having passed from the event, the media has failed to provide much, if any, substantive analysis into the true causes of the coup; rather, the media has continued to push the Organization of American States' (OAS) claim that the election of Morales was illegitimate on the basis of "the drastic and hard-to-explain change in the trend of the preliminary results revealed after the closing of the polls." However, any meaningful discussion of the conditions that led to the coup must both question the legitimacy of the OAS' claims given the history of the organization and seek to frame its analysis of the coup within the context of the economic, social, and political conditions from which it arose.

In order to gauge the validity of the OAS' claims regarding the alleged election fraud in Bolivia, one must understand the historical role of the OAS as an anti-leftist organization. When the OAS was signed into existence in 1948, "the United States hoped the new organization would serve as a bulwark against the spread of communism." Given US' intentions in founding the OAS, this fundamental opposition toward left-wing governments has permeated every level of the institution.

Courtesy: USOAS

From its founding, the OAS has been utilized by the US as a political tool to delegitimize any elected left-wing governments in the Americas; the OAS continues to work hand in hand with US officials as they are headquartered in Washington, D.C. One only has to look at the US involvement in deposing democratically elected left-wing governments in the Americas to recognize the continued role of the OAS in legitimizing US intervention into the elections of sovereign states. Perhaps the clearest example of such an intervention, one that in many ways mirrors the conditions preceding the recent Bolivian coup, is the 1954 coup in Guatemala.

Analyzing the CIA Backed 1954 Guatemalan Coup D'État

In 1951, Jacobo Árbenz, a major figure in the Guatemalan Revolution, was elected President of Guatemala by a margin of 50%. Árbenz immediately began extensive social and economic reforms, which included: "[allowing] communists in the Guatemalan Labor Party to hold key government seats", an expanded right to vote, "legalized labor unions", and "land reform legislation to expropriate idle land for redistribution to the poor." The US took issue with the inclusion of the Guatemalan Labor Party in Árbenz's government and Decree 900, which "empowered the government to seize control of idle portions of plantations." Árbenz's agrarian land reforms presented a threat to US corporate interests in Guatemala as:

"The UFCO [United Fruit Company] held about 500,000 acres of uncultivated land, in part to keep it out of the hands of competitors. The company, which had devalued the land for tax purposes, rejected the compensation then offered… by the Guatemalan government, stating it was insufficient."

Courtesy: YouTube

Under the former Guatemalan dictators, UFCO (better known today as Chiquita Brands International), had been allowed to continue its exploitative practices freely. Árbenz presented a threat to the American based corporation's profit in the country and, when the dispute between the Guatemalan government and UFCO could not be resolved, "Eisenhower authorized the CIA in August 1953 to begin planning for the overthrow of President Arbenz." Furthermore, declassified CIA documents confirm that the US worked closely with the OAS to justify taking actions against the democratically elected Árbenz administration:

"the challenge facing the United States in Guatemala was 'a new type of imperialism,' 'an open declaration of the aggressive designs of international Communism.' Therefore, the United States had to 'support' the Organization of American States (the OAS, much influenced by the United States) which fought against the 'upsetting of sovereign governments by the international Communist movement or conspiracy.'"

In 1954, the US Department of State and CIA carried out Operation PBSUCCESS, which backed the Guatemalan coup d'état against Árbenz, forcing his resignation in order to avoid further bloodshed. Operation PBSUCCESS installed the right-wing military dictatorship of Carlos Castillo Armas, which forced Árbenz to seek asylum in Mexico in order to escape persecution. Armas immediately began to consolidate power and eliminate opposition to his regime, arresting thousands of opposition leaders and opening up concentration camps to imprison political dissidents. Armas outlawed communism, labor unions, and peasant organizations and reversed the land reforms passed by Árbenz, which restored ownership of the land to UFCO.

Bolivia Under the Morales Presidency

Courtesy: Telesure

In many ways, the 2019 Bolivian coup that ended with the resignation of president Evo Morales, leader of the Movement to Socialism (MAS) party, mirrors both the conditions preceding and the events of the 1954 Guatemalan coup. Much as Árbenz worked to pass populist reforms to empower the workers and indigenous peoples, Morales too was fighting for the interests of the common man. When Morales took office, Bolivia was South America's poorest country and:

"the country had one of the most unequal income distributions in the world's most unequal region. The wealthiest 10 percent earned over ninety times more than the poorest 10 percent. Sixty percent of the population lived below the poverty line, 37 percent suffered extreme poverty, and rural poverty was almost twice that of urban areas."

In order to address this extreme inequality in the distribution of Bolivia's wealth, Morales targeted the profit of large corporations exploiting Bolivia's vast reserves of natural resources. Supreme Decree 2870 increased the taxation of natural gas companies' profit from 18% to 82%, which increased tax revenue from this industry from $173 million in 2002 to $1.3 billion in 2006. Morales used the funds generated from this tax to significantly increase social spending and spearhead efforts aimed to combat illiteracy, poverty, racism, and sexism. The efforts of Morales to improve the material conditions of Bolivians were tremendously successful:

"Real (inflation-adjusted) per capita GDP grew by more than 50 percent over these past 13 years. This was twice the rate of growth for the Latin American and Caribbean region…The country's solid economic growth has contributed substantially to the reduction of poverty and extreme poverty. The poverty rate has fallen below 35 percent (down from 60 percent in 2006) and the extreme poverty rate is 15.2 percent (down from 37.7 percent in 2006)."

Just as Árbenz managed to drastically improve the material conditions of Guatemalans, Morales too had immense success with his social, political, and economic reforms: significantly reducing income inequality, expanding access to education, and protecting the rights of all Bolivians. In 2007, Morales launched a literacy program modeled after the tremendously successful "'Yes I Can' method developed by Cuba." By 2014 the campaign had "reached more than 800,000 Bolivians throughout the country" and "illiteracy rates dropped from 13.28% in 2001 to 3.8% in 2014, when the last census was conducted."

Courtesy: The Guardian

US Motivations to Support the Bolivian Coup

Prior to his election as president, Morales had been extensively involved in the union of Cocaleros (coca growers), rising to become the General Secretary of the Cocalero Union from 1984-1994. When the US tried to eradicate coca as part of the war on drugs, Morales and the sindicatos (union) demanded "that coca should be legalized in order to create a legal market for coca leaves for traditional consumption and its legal derivatives such as tea, soap and toothpaste." The sindicatos were united through "their defence of an ancient Andean plant – an important 'natural resource' – against the 'traditional' political elite, which exploited Bolivia's riches on the back of the indigenous peoples," which ultimately proved key to Morales' electoral victory.

As president, Morales continued to fight against US imperialist attempts to eradicate the coca plant in Bolivia. "Two years after his election in 2006, Morales ordered the closing of the DEA's office in La Paz and the U.S. military base in Chimore." Morales saw this expulsion of the DEA as key to regaining Bolivia's power as a sovereign nation:

"I do not regret the decision about the DEA and the military base… The United States used the war on drugs in order to control the country's politics and loot our natural resources… Our Revolution has united the countryside and the cities, the east with the west."

However, Morales' refusal to submit to the will of US policymakers only increased their willingness to undermine his administration. A 2018 report from the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) that tracks coca production in Bolivia and Peru claimed the "ongoing coca cultivation in both Peru and Bolivia pose a threat for us as a nation, and aggravates our domestic drug addiction crisis." Following the coup and installation of right-wing dictator, Jeanine Áñez, "it stands to reason that Washington's highest priority may well be the destruction of the leftist coca growers' union and the return of the Drug Enforcement Agency to Bolivia."

The global rise in demand for lithium has led to increasing attempts by transnational corporations to extract the valuable mineral from Bolivia's vast reserves. Located in the remote southern tip of Bolivia, the "region has 50% to 70% of the world's lithium reserves in the Salar de Uyuni salt flats." Until recently, attempts to extract lithium from this region had proven too difficult due to the altitude, its remote location, and the high levels of magnesium found in the minerals as well, but the surge in demand for lithium has made the venture profitable, and large transnational mining corporations had been putting increased pressure on Morales to sign a contract allowing the region to be mined.

Courtesy: Common Dreams

In 2019, Bolivia had gotten close to signing a deal with ACI Systems Alemania (ACISA), a German mining company that supplies large quantities of batteries to Tesla, for the rights to mine their lithium reserves. After protests from the locals demanding the contract be renegotiated to increase the profit share, the deal was finally cancelled on November 4th, 2019, "due to local protests over profit sharing. The local population wanted an increase of royalty payments from 3% to 11%."

As Bolivia's first indigenous president, Morales has always sought to work hand in hand with the indigenous peoples of Bolivia to protect their rights and prevent their exploitation at the hands of corporate practices, which largely explains his readiness to cancel the government's contract with ACISA and look for more favorable contracts to mine the lithium. Throughout 2019, Bolivia had been engaging in ongoing negotiations with the Chinese company Xinjiang TBEA Group Co Ltd to mine the lithium. The terms of the agreement between China and Bolivia were far more favorable to the Bolivian economy, with China agreeing to invest twice as much into the region:

"the Chinese company Xinjiang TBEA Group Co Ltd. And the Bolivian state company Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) negotiated a deal that would have given Bolivia 51% and the Chinese 49% shares of a lithium extraction investment, an initial US$ 2.3 billion investment venture, expandable according to market demand. The project would have included manufacturing of vehicle batteries – and more – thus, adding value in Bolivia and creating thousands of jobs."

Given the US' trade war with China and the surging demand for lithium in the West, it stands to reason that the US had a lot to lose if China were to secure the rights to mine Bolivia's lithium reserves. The installation of right-wing dictator Jeanine Áñez assured the West's continued access to these minerals, aiding their future ability to secure a contract with the regime.

These threats to the US interests in the region led US politicians to voice their concerns with Morales and call for action on the issue:

"On April 12, the US Senate approved a resolution expressing 'concern' over Morales's bid for a fourth term to the presidency. They cited a referendum the president had narrowly lost in 2016 on changing the constitution — but ignored the decision of Bolivia's Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) in January 2019 decreeing Morales could stand. Amazingly, on the same day, a group of fifteen Bolivian right-wing opposition legislators published a letter to Donald Trump, asking the United States 'to intercede in Latin America and prevent Evo Morales from running again for the presidency of Bolivia.'"

How the OAS Report Grossly Manipulated its Analysis of the Data to Justify the Bolivian Coup

Immediately prior to the coup, the OAS sounded alarm bells and made claims of election fraud in Bolivia. In short, the OAS claimed that 24 hours after the first wave of results had come in they were "presented data with an inexplicable change in trend that drastically modifies the fate of the election and generates a loss of confidence in the electoral process." The claims made by the OAS served as a basis for the Bolivian military coup and the subsequent installation of right-wing dictator Jeanine Áñez as 'interim' president.

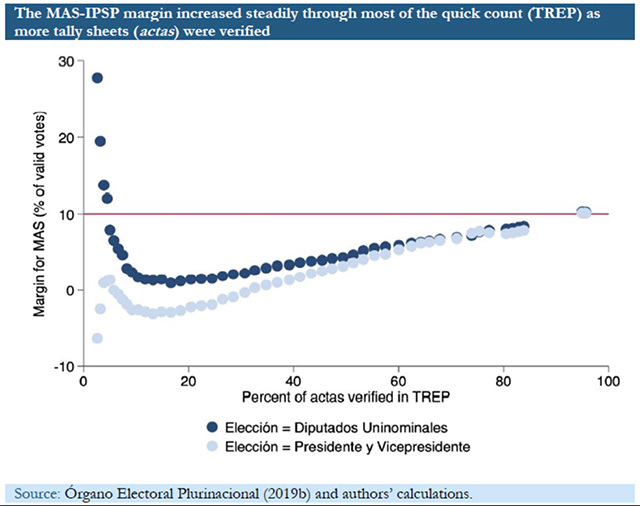

However, when considering that the results of the election very closely aligned with entrance and exit polls, the claims made in the OAS report begin to crumble upon further investigation. The entire premise that justified the report's conclusion of election fraud ignores the geography of Bolivia's more remote regions, which are last to report the voting data and overwhelmingly vote for the MAS and Morales. According to Guillaume Long, co-author of a paper analyzing the conclusions of the OAS report, "the overall trends in the results… are easily explainable and consistent with the fact that later-reporting rural areas heavily favor the MAS." The graph below illustrates that this increase in votes for the MAS and Morales is consistent with final results from rural areas trickling in after election day.

Percent margin of victory for the MAS (dark blue) and presidential race (light blue) over the percent of preliminary election results recorded by Resultados Electorales Preliminares (TREP).

Percent margin of victory for the MAS (dark blue) and presidential race (light blue) over the percent of preliminary election results recorded by Resultados Electorales Preliminares (TREP).

Courtesy: MarketWatch

Furthermore, "OAS observers can deploy only to countries that have invited them," which begs the question: if Morales intended to rig the elections to secure victory, why would he allow the OAS to monitor the election process? Not to mention that Morales had readily agreed to another round of elections in order to allow further monitoring of the process and ensure that his election was recognized internationally as legitimate.

Drawing Conclusions From the Comparisons

The conditions leading up to the 1954 Guatemalan coup and the 2019 Bolivian coup provide a startling number of similarities, hinting at the likelihood of US involvement in supporting the latter. Both Árbenz and Morales were populist politicians that represented a shift towards leftist policies, seeking to protect their peoples from the grossly exploitative practices of the imperialist West; both were replaced following a military coup by a right-wing political figure more aligned with US and Western interests. While today we know the US backed the 1954 coup in Guatemala, the full extent of their role in the 2019 Bolivian coup remains to be determined. However, the US had abundant motivations to undermine Morales and support the installation of a president more agreeable to their economic and policy interests in the region. With the perceived rejection of US hegemony in Morales' protection of coca farmers and rejection of DEA presence in the country, the US would have perceived Morales as a threat to the Western order. This tension between the US and Morales was compounded by Morales' intent to sign the mining rights of Bolivia's lithium over to a Chinese owned company, which would have likely prevented the US and much of the West from extracting these resources at a more favorable rate. Ultimately, the US played at least some role in the 2019 coup against Morales and the subsequent installation of right-wing dictator, Jeanine Áñez, but what remains to be seen is the true extent of US involvement in removing Morales from office.